How foodservice directors are changing lives and communitiesHow foodservice directors are changing lives and communities

It's a small world. With an integral role in the nutritional lives of students, employees, patients and seniors, FSDs are called upon to support, nurture and shape communities.

September 15, 2015

There’s no one way to define a community, but for most people, it means an investment in the well-being of others. With an integral role in the nutritional lives of students, employees, patients and seniors, foodservice directors are being called upon to support, nurture and shape their communities on a daily basis—both behind and beyond their own doors. For the 2015 edition of The Big Idea, we decided to take a big concept—that of community—and detail ways operators are changing the world around them for the better.

Bring in a chef to manage food allergies

A modern spin on a classic occupation helps students with allergies feel at home.

Recruit a rabbi to consult on kosher food

When the University of Colorado Boulder is missing a mashgiach, Rabbi Yisroel Wilhelm logs in to keep the kosher kitchen open.

Take food safety to the statehouse

University of New Hampshire takes student food safety all the way to the statehouse.

Incorporate local flavors

Florida Hospital Kissimmee’s Cocina 8 is catering to a diverse neighborhood.

Improve student nutrition through gardening

Los Angeles Unified School District helps students become invested in their diets through gardening.

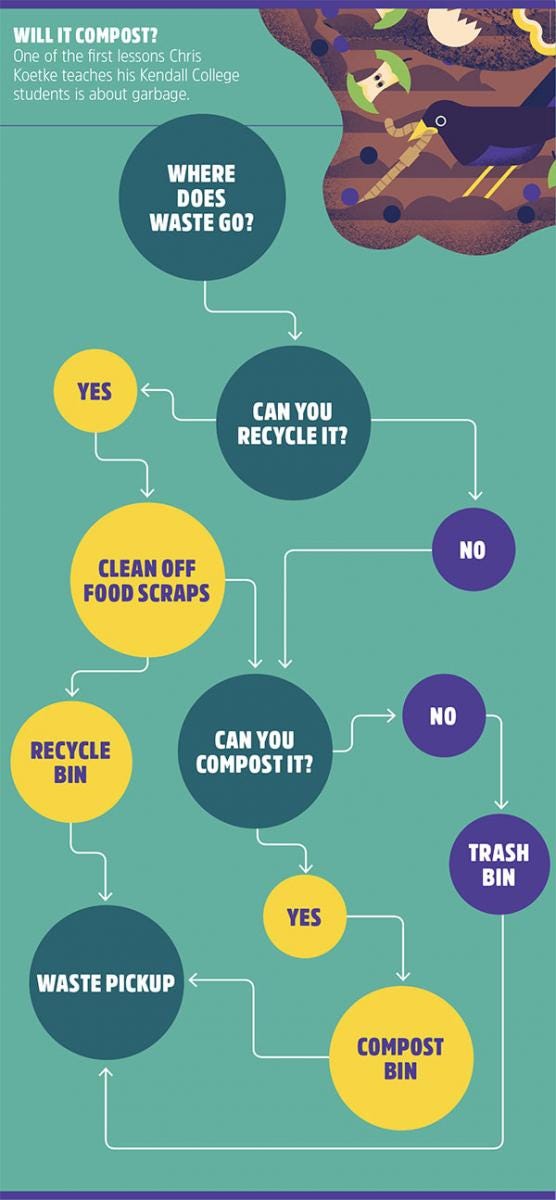

Teach students and staff to compost

Kendall College’s composting program is based on a simple mantra - Stop and think.

Use a network to promote new initiatives

Pinellas County Schools relies on a support network to feed kids with its Summer BreakSpot program.

Next: Bring in a chef to manage food allergies

Bring in a chef to manage food allergies

Two years ago, the University of Colorado Boulder Housing and Dining Services created a position seen at few other universities: chef d’aboyeur. In a traditional Escoffier kitchen, this person takes orders from waiters and shouts them out in the kitchen. But Polly Pollard acts in a slightly different role at Boulder, says Paul Houle, the university’s associate director of culinary operations. Simply put, Pollard is tasked with keeping Boulder’s allergen program a well-oiled machine.

“It’s a lot less yelling out orders and a lot more integration with our students, with our customers, with our chef, with our management team,” Houle says.

Below are just some of the tasks CU-Boulder’s chef d’aboyeur checks off her list during the course of a workday:

Communicate with manufacturers about the makeup of their products to ensure accurate menu labeling.

Communicate with parents and customers about allergy concerns via phone and email.

Examine daily menu in case ingredient substitutions arise that need review.

Input recipes into food management software program.

Meet with chefs to navigate ingredients and labeling.

Meet with campus medical-accommodations board to make sure students are living in the correct residence hall to accommodate their allergies.

Set up and execute meetings with individual students, parents and conference attendees to discuss potential allergy interactions and suggest alternatives.

Previous: How to reach, tap and foster a community

Next: Recruit a rabbi to consult on kosher food

Recruit a rabbi to consult on kosher food

The mashgiach might be the most important person in a kosher kitchen. This on-site supervisor is tasked with making decisions on whether a food or practice is acceptably kosher and must watch over the entire foodservice process. Without a mashgiach, the kitchen is frozen in its tracks—not even a burner can be lit.

That’s exactly what was happening at the University of Colorado Boulder. Without a full-time mashgiach on staff, the kosher station was relying on student mashgiachs, many of whom had morning classes. Opening for service at 11 a.m. became a considerable crunch until dining services staff settled on a solution: Rabbi Yisroel Wilhelm of the school’s Rohr Chabad Center.

Though Rabbi Wilhelm wasn’t able to physically supervise on a daily basis—after all, he had his own job to do—nothing in Jewish law prevented him from watching via a live video feed. With three cameras strategically in place (one focused on the walk-in, one directly on the door and one on the prep area), he’s able to start supervising as early as 8:30 a.m., says UC-Boulder Associate Director of Culinary Operations Paul Houle.

“With whole-leaf lettuce, [the chef] would actually wash it and hold it up to the camera, and [the rabbi] would give her a thumbs up or thumbs down,” Houle says. Meat preparation still was verboten until a mashgiach arrived on-site, but the staff was able to get much of the daily mise en place out of the way when Rabbi Wilhelm began supervising about 18 months ago.

UC-Boulder since has hired a permanent, nonstudent mashgiach, so Rabbi Wilhelm’s kitchen duties have been significantly pared back. He still logs in if the mashgiach, who lives in Denver, is late for work or needs to leave early. Rabbi Wilhelm also knows how to handle the occasional technology fail.

“[The system] was offline, and the chef was like, ‘Paul, what do we do?’” Houle says. “I was like, ‘Give it about five minutes, I can guarantee that rabbi will be here.’ And literally a minute later [Rabbi Wilhelm] had picked up the phone and was like, ‘I’m on my way.’”

Previous: Bring in a chef to manage food allergies

Next: Take food safety to the statehouse

Take food safety to the statehouse

The University of New Hampshire takes great pride in its allergen program. Students can call ahead to order special meals for pickup, staff members build a personal relationship with diners and all managers and supervisors undergo an AllerTrain certification program. But the worst still can happen.

Last year, UNH Director of Dining Hall Operations Jon Plodzik partnered with Dartmouth College to endorse Senate Bill 194, which covers college and university epinephrine policies. The law, which went into effect this July, allows schools to establish their own guidelines for administering the injections, which can have a lifesaving effect for those experiencing a severe allergic reaction. Plodzik says the new legislation is crucial to his Durham, N.H., operation.

“This could be [a diner’s] first reaction that they’ve ever had. It could be that they didn’t bring their epi pen because they didn’t realize they were going to be eating with us,” he says. “If medical care was delayed getting to us because of the weather conditions, or if they had trouble finding the location where the student was having the reaction, that could really be fatal.”

It’s better to be safe than sorry. If epinephrine is administered to someone who isn’t actually having a reaction, Plodzik says, “it would be the same as having two quick cups of coffee.”

Previous: Recurit a rabbi to consult on kosher food

Next: Incorporate local flavors

Incorporate local flavors

Bacalao, mofongo and tripleta. You’re not likely to find any of these dishes at a Mexican restaurant. But Cocina 8, the cafeteria at Florida Hospital Kissimmee’s new tower, serves customers and patients who enjoy these Spanish, Puerto Rican and Colombian dishes, and the culinary team keeps their unique palates in mind when creating new menu items.

“In order to incorporate all of the countries as well as the Latin flavor, instead of doing one specific cuisine, we decided to do … a fusion type of food,” says David Trinkle, foodservice and clinical nutrition manager. “Not just the Spanish, not just the authentic Latin, but also American flair.”

Surrounding apartment complexes and communities may be enticed to visit Cocina 8 after work for takeout entrees such as rotisserie chicken, but the cafeteria has been operating under a test-kitchen model since it opened in July. The goal is to perfect its offerings before expanding Cocina 8’s marketing reach, says Lorenzo Brown, the hospital’s dining services manager.

“Our vision is really to create a destination for the community to go, so that there are healthy options where you don’t have to compromise taste or appearance of food,” Brown says. That model has business booming—retail sales are up between 160 percent and 190 percent over the previous Kissimmee facility, Trinkle says.

“[Our staff is] teaching me the authentic way of making these dishes from Puerto Rico,” he says. “It’s a learning curve for me too, since I’m not Latin.”

Previous: Take food safety to the statehouse

Next: Improve student nutrition through gardening

Improve student nutrition through gardening

In a school district like Los Angeles Unified, it’s all about the numbers. Some 1,000 schools and 850,000 students factor in to the day-to-day operations, says Conrad Ulpindo, director of nutrition education obesity prevention for Los Angeles Unified’s health education programs. So while school gardens, including the Mark Twain Middle School Secret Garden, are found at 75 percent to 80 percent of LAUSD sites, there’s no way they can provide enough produce.

Instead, the gardens fill another role. “We definitely leverage them as a means to introduce the students—and even the community and parents—to new kinds of fruit, vegetables and herbs,” says Manish Singh, LAUSD food services regional manager. “[We show] how they can use new recipes which are more healthy, more nutritious, and make them aware of the fact that, hey, vegetables can be fun.”

Because the SoCal climate means gardening is a year-round affair, the district relies on more than current students and parents—though that group, along with staff members, is the core of the operation. “All of the parents of those kids who are grown up [and] in high school and college now ... they’re the ones sustaining it,” Singh says of volunteers in his area.

Last year, Ulpindo applied for a grant from nonprofit The Kitchen Community to establish 41 state-of-the-art gardens; many will be built and planted in the coming school year. An expanded farm-to-school program, too, will help grow students’ investment in their diets.

The Secret Garden construction plan

Existing items:

A. Classroom building

B. Chain-link fence

C. Asphalt paving

D. Metal bench

E. Grape arbor (approximate location)

F. Tree, shrub or vines to remain

Construction legend:

1. Garden entry gate and welcome sign

2. Garden pathway (compacted native soil with wood chips)

3. Wooden picnic tables, five total

4. Raised vegetable bed

5. Planting area with amended soil and spray head irrigation

6. Environmental education sign

7. 'The ruins' interactive archeology dig

8. Propagation area with planting tables

9. Material storage area

10. Sundial with boulder seats

11. Outdoor classroom with wooden bench seats

12. Outdoor performance area with hay bale seating and stage area

13. Poured-in-place concrete seatwall

14. Apple-tree espaliers

15. Greenhouse for plant propagation

Previous: Incorporate local flavors

Next: Teach students and staff to compost

Teach students and staff to compost

“I’m clearing plates or something; I could take all that and say, ‘What the heck, who cares?’ and put it all in the garbage. Or I could take that extra step and separate it into a container for compost.”

That’s the decision-making process foodservice workers go through every day, says Chris Koetke, VP of Kendall College School of Culinary Arts. This small decision makes a big difference at a facility that produced 350 tons of waste in 2014—210 tons of which were diverted into compost.

Because Kendall’s campus is smack in the middle of Chicago, Koetke had a few urban hurdles to scale in implementing the composting program. “We discovered a lot, things like how air moves through Kendall College,” he says. “When they would empty the compost, we discovered that the whole building would smell like compost. And that was not ideal.”

The school’s waste–management servicer also hauls away its compostable materials, which are separated into biodegradable bags and composted at one of its facilities. But the first step in the process, Koetke says, is helping diners and workers understand that their individual environmental actions have an effect on the entire community.

“Put it in perspective so the customers and employees are like, ‘Wow, I’m part of that, and holy smokes, I’m making a big difference. And by the way, I might as well scrape my plate, because I’m part of that now,’” he says.

Previous: Improve student nutrition through gardening

Next: Use a network to promote new initiatives

Use a network to promote new initiatives

In 2014, Lynn Geist’s Summer BreakSpot program, which serves free breakfast, lunch and snacks to children ages 18 and under as part of the USDA Summer Food Service Program, went from about 30 sites to nearly 100 after absorbing sites from a sponsor who dropped out. That’s 3,300 daily breakfasts and 6,000 daily lunches, says Geist, the Pinellas County Schools’ director of food services.

A big part of Geist’s success depends on her community connections. “You just kind of need to feel out who’s out there who might be willing to help,” the Florida operator says. “You’ll find that there’s help in places that you weren’t expecting it.” Here’s how some of her network has come together to market Summer BreakSpot:

1. Pinnellas County Schools

“We have a flyer that we send out about a month before school ends that goes to all elementary schools, and then they’re in the office of the middle and high schools, [as well as] our website,” says Geist.

2. Juvenile Welfare Board

“They’re even doing some pilot programs to help our kids and develop new things for next year,” she says. Geist’s also appeared in videos for the JWB, which has its own childhood-hunger initiative.

3. Local TV

Geist has spoken about the fact that children don’t need to sign up for the free Summer BreakSpot program; they just need to show up.

4. State of Florida

“They have a public service announcement that I’ve been seeing all summer that started up in May,” Geist says. In addition, volunteers from community groups walk the neighborhoods to distribute door hangers and talk with local residents.

5. Churches

In addition to faith-based groups distributing flyers to their congregations, the sites are a huge part of Geist’s operation. “They’re not only willing to open their doors for a summer [meal] site, they’re doing activities. They bring the kids in and here I’ve got three meals for them,” says Geist, who has Summer BreakSpots at about 30 churches.

6. Tampa Bay Network to End Hunger

Geist herself addresses city council meetings, but this group also spreads the word at meetings throughout Pinellas County.

7. SummerFoodFlorida.org

The state-run website contains a wealth of information about BreakSpot sites and where to find them. Residents also can download an app for mobile info.

8. USDA

“This summer is the 40th anniversary of the summer foodservice program, and after 40 years, people are still saying ‘I’ve never heard of it,’” Geist says. The government body has realized this and increased its marketing and informational output.

Previous: Teach students and staff to compost

About the Author

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)