Hospital takes 52 weekly steps to healthier dining

One change a week for a year has led to a much improved wellness profile for the University of Wisconsin Hospital’s cafes.

Like many healthcare institutions, the University of Wisconsin Health wants to do the right thing when it comes to encouraging healthier eating habits among customers. But it also knows it has to tread lightly in what is a stressful environment that can lead staff and visitors to comforting but less than healthful dishes.

An early experiment removing sugared beverages and deep fryers resulted in some customer pushback, so the dining team, led by Director of Culinary and Clinical Nutrition Services Megan Waltz, decided to try a different approach.

“We started to make incremental changes over time like changing out the lettuces to something local,” Waltz recalls. “Then last January I asked my staff, ‘What if we do one change a week for the rest of the year and we promote it as something that promotes wellness?’”

They liked the idea and so the yearlong initiative was launched by dropping the price at the salad bar from $8 a pound to $4.99. The result was a 50 percent increase in salad sales for the month, to 18,000—and this past January it jumped again, to 21,000.

Aside from the price drop, it doesn’t hurt that the salads are weighed before the dressing is put on. Because of the tight squeeze and heavy traffic around the salad bar, Waltz says it made more sense to move the dressings past the weigh station to create a little more room and facilitate flow.

Other weekly changes over the course of the year—most of which were permanent after being introduced—ranged from the fairly minor, such as adding an ancient grain hot cereal to the breakfast menu, to significant ones requiring substantial changes in procedures or procurement, such as moving to exclusively using Wisconsin pasture forage beef from local producers.

One of the most successful changes was reducing the price of whole fruit from the $1.20 to $1.50 range to 50 cents across the board.

“In the first week of that we went from selling about 50 pieces of fruit a day to 500,” Waltz recalls.

Pricing is a key component of the strategy, with healthy selections like bottled water and sparkling water and low- or nonfat yogurts also being discounted. At the grill, the vegetarian bean burger is now the lowest priced choice and the beef the most expensive.

The moves “really started to help people see all the things we were doing in a positive way instead of viewing it as taking [things] away, which I think often happens when you remove things like fryers and sugar-sweetened beverages,” Waltz notes. “So it really helped change the mindset.”

The Flavor My Plate program brings dishes based on recipes from different UW Health dining staffers to the cafes on a biweekly rotating basis.

The Flavor My Plate program brings dishes based on recipes from different UW Health dining staffers to the cafes on a biweekly rotating basis.

Actually, there were some removals, but they were done unobtrusively. For example, the soft serve ice cream machine quietly went offline one day, supposedly due to mechanical breakdown—and never came back.

There was some pushback, Waltz admits, but the story for those who asked was that the unit was “waiting for parts.” That wasn’t a total fib, she says, because it was quite old and prone to breakdown.

A baked potato bar that was prone to encouraging unhealthy choices—customers routinely packed their spuds with sour cream, butter, cheese and so forth—was pulled in the summer to expand the increasingly popular salad bar.

“We told people we’d reconsider it in the wintertime when the weather got colder because baked potatoes aren’t a summer food and we needed more space [in the summer] for the salad bar,” Waltz says. “There were a few requests in the fall for it, but we haven’t added it back.”

Some changes didn’t have quite the anticipated impact, Waltz concedes. For example, the introduction of more gluten-free selections did not produce a lot of additional sales, perhaps because some of the other changes satisfied that demand.

Aside from the salad bar, the most popular station in the café is the entrée station, where one can still get those stress-soothing comfort foods—but with a difference, as reflected by its being renamed Farm to Table (one of the 52 weekly changes).

“We have tried to add more vegetarian options there, using our local farmers for vegetables,” Waltz says.

The chicken used is now all antibiotic-free and humanely handled, and all sandwich meats will be antibiotic-free within the next few weeks as well.

The determination to reduce sodium levels in the food served led to one of the most successful menu program additions in the café. Termed Flavor My Plate, it takes advantage of the dining staff’s wide cultural diversity to collect their suggestions for a series of ethnic dishes that are then served on a rotating basis in the café, dishes that emphasize spices rather than salt for flavor.

The staffers actually create the dishes in the kitchen, and these are then taste tested and the culinary staff determines whether they are feasible for volume production.

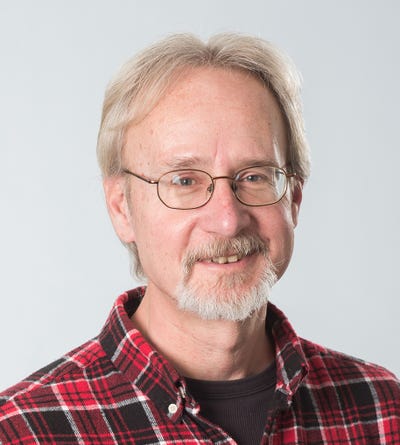

UW Health Director of Culinary & Clinical Nutrition Services Director Megan Waltz (center) with Executive Chef Ellen Ritter (left) and Sous Chef Lisa Boté.

UW Health Director of Culinary & Clinical Nutrition Services Director Megan Waltz (center) with Executive Chef Ellen Ritter (left) and Sous Chef Lisa Boté.

“It became an employee engagement thing for the staff as they compared recipes and ways of preparing similar dishes,” Waltz recalls. “It became a lot of fun and also educational for us. And it was a huge hit with customers in the café.”

The different ethnic dishes were rolled out a couple of times a week in two-week increments so a couple of dozen ended up being served over the course of the year. Some proved so popular that they have become part of the regular menu cycle on the entrée and soup stations, and Waltz is now exploring opening a regular international food station.

Some of the 52 initiatives were designed to support the wider community as well as to promote internal wellness. For example, cookie production was outsourced to a local program called Just Bakery that teaches recently released prison inmates baking skills.

The program is actually a win-win for everyone, including the UW Health bakery staff, which found cookie production—the place goes through more than 3,000 a week—tedious, and also for their management, which was able to reassign the time formerly devoted by skilled bakery staff to routine in-house cookie making to activities that make better use of their talents.

Another community engagement initiative implemented in the yearlong program brings local restaurateurs to the hospital café to promote their establishments.

The 52-week program is not being continued in 2017. Waltz admits the ideas began to peter out as the year wound down, as the most obvious changes were implemented.

Instead, this year the hospital embarked on a Harvest of the Month program that showcases a different local produce item each month. January featured cabbage, with winter squash and root vegetables following in February and March, respectively. The initiative includes education programs with the hospital’s ambulatory dietitians demonstrating how to work with the month’s featured product.

Waltz oversees six food venues at UW Health, including the main café and a smaller one at the children’s hospital, plus two cafes and two kiosk-type coffee shops.

The UW medical campus incorporates the medical school as well as schools of pharmacy and nursing, so the hospital cafes see not only onsite staff and visitors but also students from those schools.

“We’re kind of the one place to eat on this side of campus,” Waltz offers. The main university campus of course has its own dining services.

The impact on financials has been modest. While all the price cuts have reduced check averages as customers flock to take advantage, it has been made up in volume, Waltz says, with transactions up by about 500,000 over the course of 2016 as compared to 2015, going from about 2.2 million to 2.7 million, and Waltz says this year is likely to surpass three million.

About the Author

You May Also Like